On The Road Again

Civil War, The Hitcher and The Sweet East fragmented, Between Intervals and Whatnot

Alex Garland’s Civil War (2024), unfortunately, contains no mice.

Barthes describes moviegoers who sit on the front row as either being children or film buffs, I would maybe also add people who sit on the sides rather than the middle in those categories. I never sit in the center row of the theater, except when I’m on the front row. I’m always on the sides, turning my head towards the screen, looking at it not as if the image was ever consuming, but rather a thing in the room.

It was on the right-screen-side that I found myself watching Alex Garland’s Civil War (2024). First on the lower middle rows of the left side of the theater, until a mouse climbed the seat next to me, forcing me to move to the other side of the theater, which was mouseless (I feel like I have to clarify that I was not scared of the mouse, but that I simply did not feel like sharing my popcorn that day.) On the right side of the screen, I looked at the film through yet another angle. I got to the room early, so I experienced three different lighting settings in the screening: the first one completely lit, the second one dimmed for the previews and the third one completely dark except for the screen and the mandatory exit signs. The mouse undoubtedly experienced the film from virtually every space in the room—and I would assume mostly from the floor of the theater, under the seats—and I wondered how Barthes would have classed it.

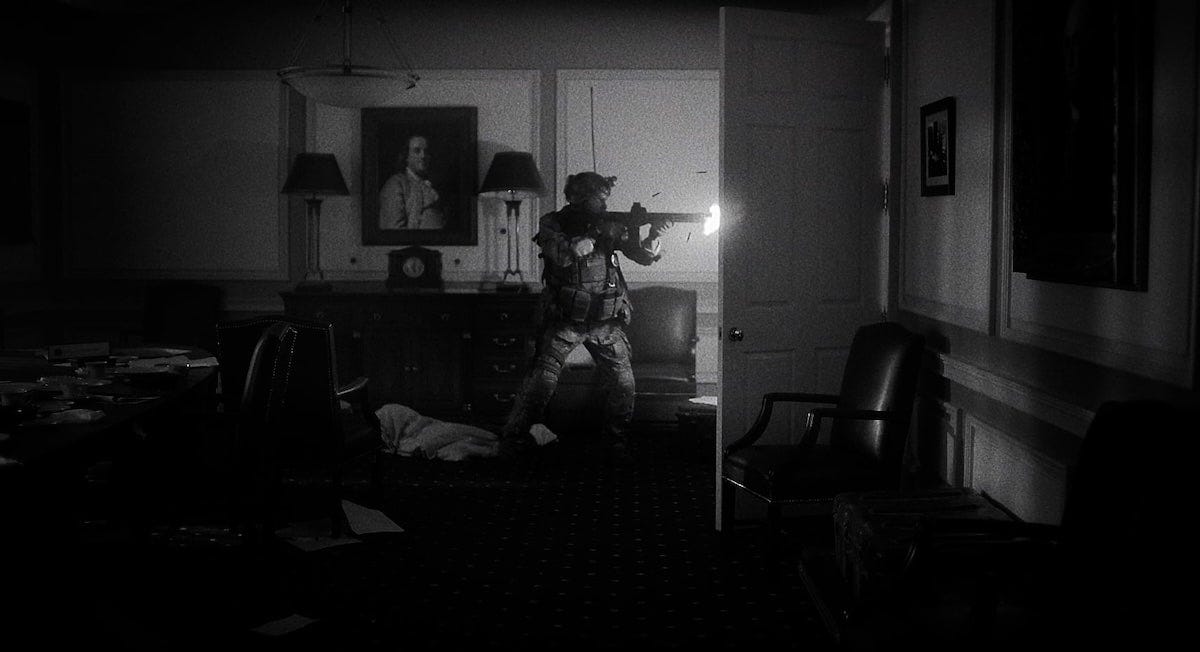

Civil War is a political film, but only because it is set against the background of a war fought between two opposing sides: the Western and Government Forces. The film follows three members of the press on a journey from New York City to Washington D.C. to interview the president—in this, Civil War is rather a road movie with a political background. By being on the road the film allows itself to look at its constructed political scenario as a series of disconnected scenes, as stilled images. “Our job is to photograph, it is up to the viewer to do the thinking.” Says Lee Smith, a war photographer and the protagonist of the film, played by Kirsten Dunst. In the little criticism I read on the film, panning it as critically empty, or too politically obvious, Dunst’s point seems to be lost.

Civil War’s background is a disaster. Besides knowing that Texas and California have seceded and joined forces against a supposedly tyrannical government, the film does not contain any politics of its own. There are obvious analogies to be made between the scenario of the film and the more immediate political situation of America, but these analogies are not necessary for the structure of the film to work. What works in Civil War is the fact that it does not care if this contingency is real or not, it plays it out as a disaster in need of documentation.

Civil War is, above all, a great action film. It does not offer a critical point of view of the scenario it creates, nor is its scenario a critique of anything real, although through its emptiness (and the roads, towns and places mostly are empty) does allow for a sort of immediate projection. The press’ lack of involvement in the recording of the war is maybe one to be criticized, but what works in Civil War is that the press seemingly does not have any values besides the need for adrenaline. They are action heroes devoid of any power to change the situation and who can save only but themselves.

That two of the main characters of the film are photographers is an interesting point of the film. As the two approach a fallen helicopter on an abandoned supermarket parking lot, Kirsten Dunst’s character tells her involuntary pupil it will make a good picture. After the process we are faced with the result. The movement halts and the screen turns to black and white, we watch a photograph on screen.

“What happens when the spectator of film is confronted with a photograph?” Asks Raymond Bellour in his essay “The Pensive Spectator.”

“The photo becomes first one object among many: like all other elements of a film, the photograph is caught up in the film's unfolding. Yet the presence of a photo on the screen gives rise to a very particular trouble. Without ceasing to advance its own rhythm, the film seems to freeze, to suspend itself. inspiring in the spectator a recoil from the image that goes hand in hand with a growing fascination. This curious effect attests to the immense power of photography to hold its own in a situation in which it is not truly itself. The cinema reproduces everything, even the fascination the photograph exercises over us. But in the process, something happens to cinema.” (Raymond Bellour, “The Pensive Spectator,” in The Cinematic, ed. David Campany (Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 119.)

In these stilled moments of the film, nothing is hidden, it is simply not shown. Even if film and photography are not “real,” it does not mean they cannot contain a semblance of “truth.”

The film chooses to photograph certain moments to show what this fictional war could look like if it was actually happening. The last shot of the film is a photograph of its culmination, the credits roll as we see more shots of the same scene. It is similar to the freeze-frame at the end of The Breakfast Club (1986, John Hughes), except we are not so much left to wonder what will happen on Monday, but we rather know that there is a future set after the film. There is one interesting scene in which the young photographer develops a batch of film and scans it with her iPhone. The camera focusing on the phone’s screen and showing us what had been shot in the scenes we had just watched. The last shot of the film, and the credits as well, tell us that there was always something outside of it.

Thinking back on the scenario the film constructs, the places of Civil War are described with military precision: location, date, hour. And although the scenes of the film may be all interconnected by the roads in-between each place, they feel fragmented. As there is a lot we don’t know about the political state of the world of the film, a blanket of negative space covers everything. If all the characters of the film are aware and informed on everything that is happening, then how could we ever begin to ask for an explanation of everything if there is no one out of the loop? “The world worlds and is more fully in being than the tangible and perceptible

realm in which we believe ourselves to be at home. World is never an object that stands before us and can be seen.” Writes Heidegger in “The Origin of The Work of Art.” I love overexplained films, but I also recently read something from Thomas Elsaesser stating that “world” cinema differs itself from its Hollywood counterparts on the basis of its realism—that Alex Garland is English maybe offers some kind of background to the film’s lack of explanation.

The Hitcher (Robert Hammon, 1986), which I watched at Paris’ Le Champo movie theater, the week after Civil War had been released, takes place nowhere. Every road, gas station and diner in the film seems to be surrounded by nothing. There are no town names anywhere. Its locations seem to be created out of thin air only to be stages, the film being set in “space” rather than in “places.” Having watched both close to one another, it became hard not to compare them. The road in both films seems to remove any weight of the real world outside of the films from themselves.

Taking place in the East Coast of America, The Sweet East (Sean Price Williams, 2024) is a road movie with almost no traveling. While in most road movies each location is separated by the journey taken in between, The Sweet East offers the East Coast as one continuous location. In the film, which is a rough adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, time and place cease to “really” exist. The journey of the film follows the opposite route of Civil War, it goes up from D.C. rather than down to it. By comparing the title of the two films something interesting occurs: while The Sweet East is unapologetically a film about its location, Civil War is not a film about where it takes place. The Sweet East’s political critique is satirical, with each sequence of the film seemingly taking place in different political events of the last six years, but all during one summer. Any attempt at realism, seriousness or continuity is destroyed. Who cares? Nothing matters, whatever seems, at times, to be the stance all three films want us to take.

I digress. I can’t help but to allow myself to be taken by the power cinema has to conjure analogies out of thin air.