After an emblematic cutscene, the game gives me control over my character once again. I move the joystick 360 degrees making my character spin—If this were a film, I would have broken the illusion with my poor performance.—I resume the game as usual: following objectives, defeating enemies, collecting loot. I die at a few points and I am allowed to restart from a checkpoint as if nothing happened, but I ponder on the fact that at any time the protagonist can die, and that if that happens, it is my fault.

My many deaths are generally met with disregard. In Dark Souls (Bandai Namco, 2009) the screen tells me “YOU DIED.” In the Grand Theft Auto series (Rockstar, 1997-20xx) it says “Wasted.” But in Metal Gear Solid 1 (Konami, 1999), Otacon yells Solid Snake’s name when I let the character die. It is as if my importance as a player is dictated by how the game , and I, perceive my defeat. In God of War (Sony, 2018), Mimir, whose head we carry on our belt as a companion, says something like “Off your back Kratos” when our limp body hits the ground. I am allowed to continue because there are more checkpoints and cutscenes I must reach. The loading screen offers me combat tips and asks me to press “A” when I am ready to return.

These are all elements I somehow have to consider. I try to make a connections to cinema, but the interactivity and the possibilities a piece of software gives us to break it apart make me reconsider. Modes of distribution and viewing are important, a video-game often turns the player into a spectator only to give them back a sense of agency.

In 2007, shortly after seeing my Grêmio lose to Boca Juniors in the Libertadores final, I replay the match on a modded version of Winning Eleven 9 (Konami, 2005) for the PlayStation 2. Despite the now horrible graphics, I score the impossible four goals on the second leg of the finals and temporarily mend my young and broken heart. My dad gives me an article in a magazine to read, it is on how video-games are taking over the film industry, how games are now the new films. Grand Theft Auto IV (Rockstar, 2008) is set to release the next year, but tomorrow is a school day, and the fans of Internacional, my team’s rival, will make fun of me for the loss.

Super Mario Strikers (Nintendo, 2005) for the Nintendo GameCube is a Super Mario soccer game with two endings: losing or winning. Cinema, art and literature give themselves away to criticism because of their openness or ambiguity. “Why is Megalopolis (Francis Ford-Coppola, 2024) so “bad”?” is a question that comes to mind when I recall Coppola’s oeuvre. When a game is “bad,” it is generally unplayable. I sometimes feel like the only way I have of talking about video-games is to compare them to other visual media. What lies between losing and winning?

I recently explained to my partner what it was like to teabag someone in a Halo 3 (Bungie, 2007) Deathmatch. “Art is the living and concrete proof that man is capable of restoring consciously, and thus on the plane of meaning, the union of sense, need, impulse and action characteristic of the live creature.”1 Writes John Dewey in Art as Experience. Video-games suddenly open up as a living space. Where the idea of ‘everything,’ found in the spaces between the senses, seems possible. But how do we exactly put everything together? “The answers cannot be found, unless we are willing to find the germs and roots in matters of experience we do not currently regard as esthetic.”2 He continues.

I played God of War: Ragnarök (Sony, 2022) thinking through my own notions of cinema. More specifically the nature of cinema being defined by its limitations, that the complexity and expanse of experience could never be fully translated to the medium, but only represented in reduction. It is hard not to play in, and sometimes watch, a fully rendered 3D environment set in the realms of norse mythology and not, for a moment, disregard my ideas of limitation in media. “The difference between the several languages, therefore is not a matter of different sounds and marks, but of different world conception.” Writes Ernst Cassirrer in Language and Myth. If “everything” is possible in 3D, why stop at real life? “The nature of concepts, therefore, depends on the way this active viewing is directed.”3 He answers.

The limitation of the video-game is virtually inexistent when it comes to its frame rate. While cinema hides a moment between each one of its recorded frames, and visually disregards any space not in front of the camera, most modern video-game consoles and PCs have used their increasingly high frame rates to create worlds where it seems like nothing is hidden from the player’s camera. If a “flicker [in cinema] is produced by the shutter that regularly conceals the moment when the filmstrip moves past the aperture, thereby eliminating the blurred image this movement might cause if it were visible,”4 then what is the modern video-game trying to hide? A great amount of text.

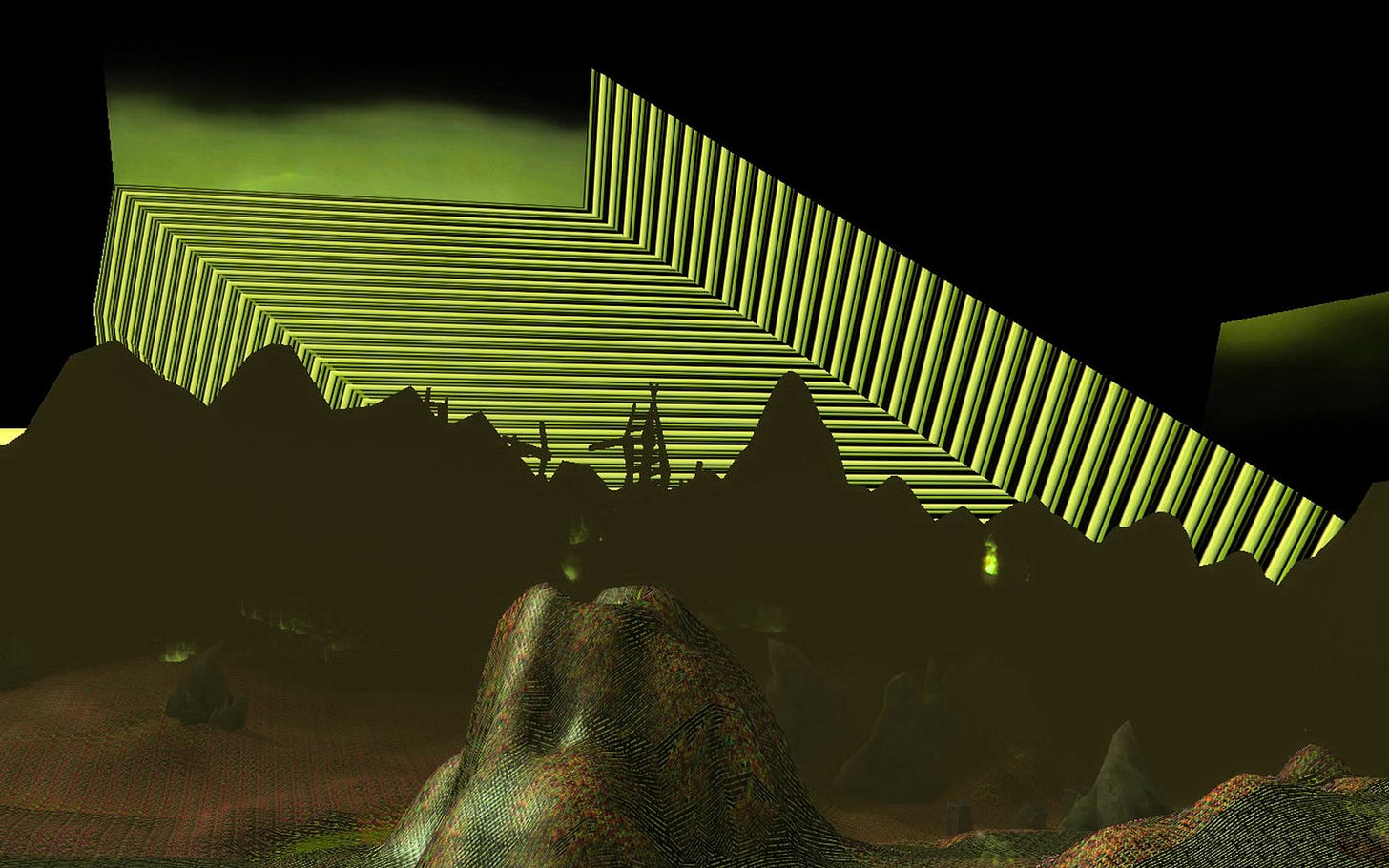

Video-games hide their mechanisms in plain sight. Each wall, platform and enemy hides an untextured and hollow skeleton, sometimes accessed through player exploitation or on accident through a badly written code. It makes me think of Eron Rauch’s Glitchscapes (2005-2009), an exploration of the beauty of the hidden and broken landscapes of World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004). And also every Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996) speed -runner, breaking through the walls of Princess Peach’s castle. The limit is, by no means, what we can access without effort.

But the limitation in video-games is, at the same time, rather close to the linguistic limitations that cinema suffers from. The two new God of War installments ask: “How do you tell a tale of fatherhood?” Many films, from Robert Benton’s drama Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) to Dennis Dugan’s comedy Big Daddy (1999) starring Adam Sandler, have attempted, succeeded and failed at answering that question. The answer to such a demand is limited by the retelling of an experience that may not fully encompass the problems of its subjects, and doubly limited by the incapacity a visual medium has in translating that which is no longer in front of us, or never was. But it is hard to say that God of War feels like a reduction of the complexities of its subjects. A limit, it seems, doesn’t always point to something smaller.

To limit something does not mean to make it smaller than its subjects. It also does not mean it cannot stop at the limit of reality, or go beyond it. That the climax of God of War: Ragnarök’s strategy takes place after the breaking of a huge, insurmountable wall, means something. To go beyond the wall is to admit to your son Atreus that closing one’s heart to the suffering of the world was wrong, that feeling how we do to the loss of innocent lives makes us who we are, it gives us our strength.

The game’s message is about realizing that the way we limit the understanding of ourselves can be expanded, that prophecies do not mean fate. That I am playing the game and controlling these flawed characters also makes me realize I want to be better, and not only at defeating enemies with my Axe and Blades of Chaos. In the written development of a character I helped build, the expansion of “the limits of my language” and “the limits of my world”5 suddenly feel within reach.

There are no cuts in a game like God of War. The protagonists are always the focus of the virtual camera as it follows all of their actions. I can’t decide if I am an actor in this film or its director, despite not having created or thought about any of these environments. It sometimes feels like work and the cuts in the editing only come if I make a mistake and die.

Many of the things I say about God of War I maybe would not write if this weren’t my first attempt at critiquing a video-game. Its seems to me that video-game critics do away with elements of the game they find unimportant. That good criticism can see past gameplay faults for a great story. But I am still stuck on thinking about mechanics. I mostly remember playing The Last of Us Part II over a weekend at the end of 2020, cooped up at home once again. To talk about the gameplay would not describe how much the experience of finishing it meant to me. There is a lot to explore in these cinematic games, but the ending is the same for everyone. In a world filled with choice, it feels positive to be told what to do, to feel good in the repetition caused by each enemy encounter and quick-time event.

The end of God of War: Raganarök plays as the credits roll on the left side of the screen, but I am still Kratos. I walk down a mountain, as several of the other characters of the game offer their last remarks on my adventure. As I exit the temple, all the side quests I did not complete are suggested to me. The credits rolling as the game is still playable offers some kind of value to my experience. There is no black screen at the end of the credit sequence, I must decide for myself when the experience is over, and it may be beyond the press of a power button.

REFERENCES:

Cassirer, Ernst. Language and Myth. Germany: Dover Publications, 1946.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. New York: TarcherPerigee, 2015.

Gunning, Tom. “Flicker and Shutter: Exploring Cinema’s Shuddering Shadow.” In Indefinite Visions. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. UK: Harcourt Brace, 2015.

John Dewey, Art as Experience. 2005, 26.

Ibid. 11.

Ernst Cassirrer, Language and Myth. 1943, 31.

Tom Gunning, “Flicker and Shutter: Exploring Cinema’s Shuddering Shadow.” 2022, 55.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico Philosophicus. 2015, 86.